The Big 3 of Altitude Sickness: AMS, HAPE, HACE

Altitude Sickness or AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness) can go from annoying to critical. What is HAPE and HACE? What are the symptoms and how to treat it? As I was dealing with AMS myself several times in Mexico and Chile, I decided to write down all the essential information for you and something on top of that. Interested? Keep reading.

1. What is altitude sickness (acute mountain sickness)

When being higher than 2 400 m (8 000 ft), the human body may experience hypoxia, which is a medical term for a shortage of oxygen supply in human organism. At an elevation of 3 000 m (10 000 ft), the amount of oxygen in the air drops to just a two-thirds of what it is at sea level. The body´s reaction to the shortage of oxygen is called altitude sickness, mountain illness, or a medically more accurate variant, acute mountain sickness (AMS).

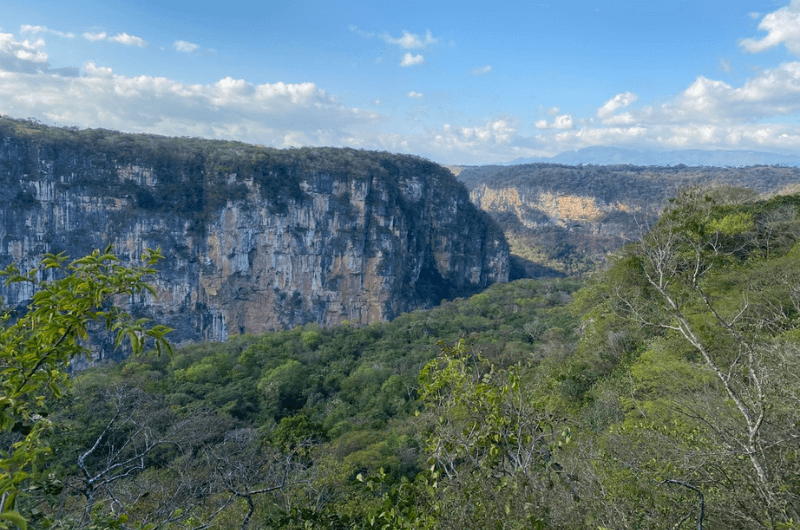

All of this may happen to less experienced climbers. Usually when you ascend too quickly, without proper acclimatization, or when you sleep at high elevation. AMS may take in a number of symptoms, some being mild and some pretty ominous. Let’s take a look at them… but first, take a look at this handsome hiker.

Read also: 10 Best Hikes in Mexico: Mountains, Temples and Waterfalls

2. Altitude sickness symptoms

Altitude sickness manifests itself in various forms, depending on its severity. However, it can be tricky, as the first occurring symptoms are basically the same as when you have a hangover:

- headache

- feeling sick (followed by vomiting)

- drowsiness and dizziness

- loss of appetite

- shortness of breath

Mostly it gets worse at night, which can be dangerous, especially when hiking on your own. When not treated, altitude sickness may lead to some serious health complications, unconsciousness, or even death. This is not to scare you, but to make you aware… believe me, when my wife experienced elevation sickness, I was desperately looking for an article like this.

3. The health risks of altitude sickness

The health risks vary, from mild AMS to HACE and HAPE which can be deadly. Let’s now take a look at those acronyms to make it less scary.

AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness)

What it is:

AMS is the most common. It appears when you are going up too fast without proper acclimatization. It's just a temporary inconvenience, but you should pay attention to it.

What it looks like:

Acute mountain sickness leaves no permanent damage, but it can be pretty annoying, I’m telling you. The headache and drowsiness (luckily) prevents you from going further. Add the nausea and vomiting in your tent and it sounds like a nightmare.

What to do with it:

The best thing you can do is either descend a bit (at least 500 m; 1 600 ft) or stay at the same spot for two or three days to get used to the elevation. Do not in any case continue to ascend until you are fully recovered! This one is tricky and looks harmless, but it can get worse so quickly.

Read also: How is Traveling in Mexico During COVID-19?

HAPE (High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema)

What it is:

HAPE means your body builds up excessive fluid inside your lungs, causing them to swell up. The excess fluids inside the lungs prevent oxygen from circulating your body. And I hope you know that you really need the oxygen circulating. The occurrence of HAPE is 1 per 100 climbers at more than 4 270 m (14 000 ft)—according to the CDC, which makes it quite rare, but you should know about that still.

How it looks like:

It may occur as late as several days after your arrival at high altitude. The basic symptoms are the same as AMS, just worse. At this point, the affected person also experiences shortness of breath (not caused by the stunning mountain views) and dry cough. The fatal turn in HAPE can be much faster than with HACE.

What to do with it:

The oxygen income or descent must come asap and preferably without physical exertion of the person experiencing it. At this point, you shouldn’t stay in the mountains, but seek professional medical care. If not possible, use the dexamethasone or oxygen bomb to relieve the person affected and descend immediately when possible.

HACE (High-Altitude Cerebral Edema)

What it is:

This is where it gets really serious. HACE or High-Altitude Cerebral Edema is the swelling of the brain. It may happen when the AMS is not treated and you continue to ascend, not fully recovered. Despite being the rarest form of AMS (the incidence of HACE is 0.5–1% at the altitudes of 4 000 to 5 000 m; 13 120 to 16 400 ft), you should be aware of it.

How it looks like:

HACE develops quickly, just over a few hours. The person affected usually isn’t aware of it (they will insist that they are ok) and hallucinations frequently occur at this phase, making it even more dangerous. It may cause permanent brain damage, coma or even death, when not treated immediately.

What to do with it:

Immediate descent of at least 1 000 m (3 280 ft) is crucial. There are the same rules as with HAPE: no physical exertion, use of dexamethasone or oxygen supply to ease the symptoms and seek medical care asap.

4. Altitude sickness treatment

The treatment for altitude sickness isn’t complicated, however, it’s always better to prevent it in the first place. Most importantly: DO NOT PANIC! It won’t help anyone. After you take a few deep breaths, stick to this list:

- stop and rest where you are

- do not go any higher for at least 24 to 48 hours

- if you have a headache, take ibuprofen or paracetamol

- if you feel sick, take an anti-sickness medicine, such as promethazine

- make sure you're drinking enough water

- do not smoke, drink alcohol, or exercise

- regular caffeine users should continue to do so

It’s especially younger males who make the mistake of continuing in ascend, not fully recovered. Don’t do that, it’s not heroic, it’s stupid, and it may have serious consequences. Continue to ascend only once you’re fully recovered. And that can take two or three days. You should also inform your buddy on how you feel.

Let's say you’re hiking with some stubborn mule who insists on being alright and ready to go. In that case, look after him or her and don’t believe a word they say. When the AMS is not treated, it might get worse and the person affected may have hallucinations and get disoriented. Be prepared for that. And don’t let your buddy run around in the mountains tripping and delusional.

5. Altitude sickness prevention

As I said earlier, it’s best if you don't have to worry about that at all. And don’t be cocky, the AMS can affect even trained and fit, perfectly healthy people with zero body fat. So, take the advice. First and foremost: TRAVEL SLOWLY ABOVE 2 500 m (8 200 ft)!

- don’t fly directly to areas of high altitude, if possible (it would be a big shock for your body)

- consequently, take 2 to 3 days to get used to high altitudes before going above 2 500 m (8 200 ft)

- avoid climbing more than 300 to 500 m a day (1000 to 1600 ft)

- rest every 3 to 4 days or take a rest day after long ascend

- drink enough water

- avoid smoking and alcohol

- don’t strain yourself too much for the first 24 hours

- high-calorie diet will help you get enough energy

If you had a previous experience with acute mountain sickness, consult your doctor and ask him to prescribe you the dexamethasone. It will help you relieve symptoms in case the descent is impossible at the moment. Professional climbers usually have it in their medical kits as it also helps to decrease brain swelling.

High-elevation destinations: Are you going to a risky area?

You might be surprised, but altitude sickness occurs not only in the Himalayas or other world known climbing destinations. It can catch you by surprise at your vacation trek anywhere the altitude is over 2500 m (8200 ft). Here are some massively visited high-altitude areas:

- Cusco (11,000 ft; 3,300 m)

- La Paz (12,000 ft; 3,640 m)

- Lhasa (12,100 ft; 3,650 m)

- Everest Base Camp (17,700 ft; 5,400 m)

- Kilimanjaro (19,341 ft; 5,895 m)

In my experience: Mexico (Izta- Popo National Park) and Chile

When I was in Mexico and in Chile all trails were harder than other places I’ve been before. The hike was short, just a few kilometers, but very challenging due to high elevation gain—for example Izta Popo. And just so we’re clear, I’m no wuss (as you can see in the picture below, I’m a heroic badass).

Why do some people get altitude sickness and some don’t?

The scientific research shows that experience plays no role in this. It’s all genetics. So even if you’re physically fit and young, you can have acute mountain sickness. On the other hand, you can be older or amateur and be just fine. Gender also doesn’t matter here. Basically it’s a lottery, but those who pay attention to prevention have a real chance to dodge the bullet.

Read also: Shark Cage Diving in South Africa: 3 Stages of My Heroic Descend Among the White Sharks

Pre-existing medical condition: Should I avoid high-altitude hikes?

As we said, it’s mostly random, however, you should be cautious with these medical conditions:

- heart failure

- myocardial ischemia (angina)

- sickle cell disease

- any form of pulmonary insufficiency or preexisting hypoxemia

- obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

If you are treated with some of the above, you should consult your physician when planning such hikes. Surprisingly, patients with well-controlled asthma, hypertension, atrial arrhythmia, and seizure disorders at low elevations generally do well at high elevations. It’s also a good idea to think carefully about high-altitude traveling when you're a diabetes patient or pregnant. It may be safe, but you should be aware of the risks and prepared for the emergency, if the AMS occurs.

You can support our blog

If you like our posts and would like to get some awesome bonus material like itineraries, our e-book or exclusive content, you can check out our Patreon memberships. If you decide to show your love, thank you!

Comments

Thoughts? Give us a shout!